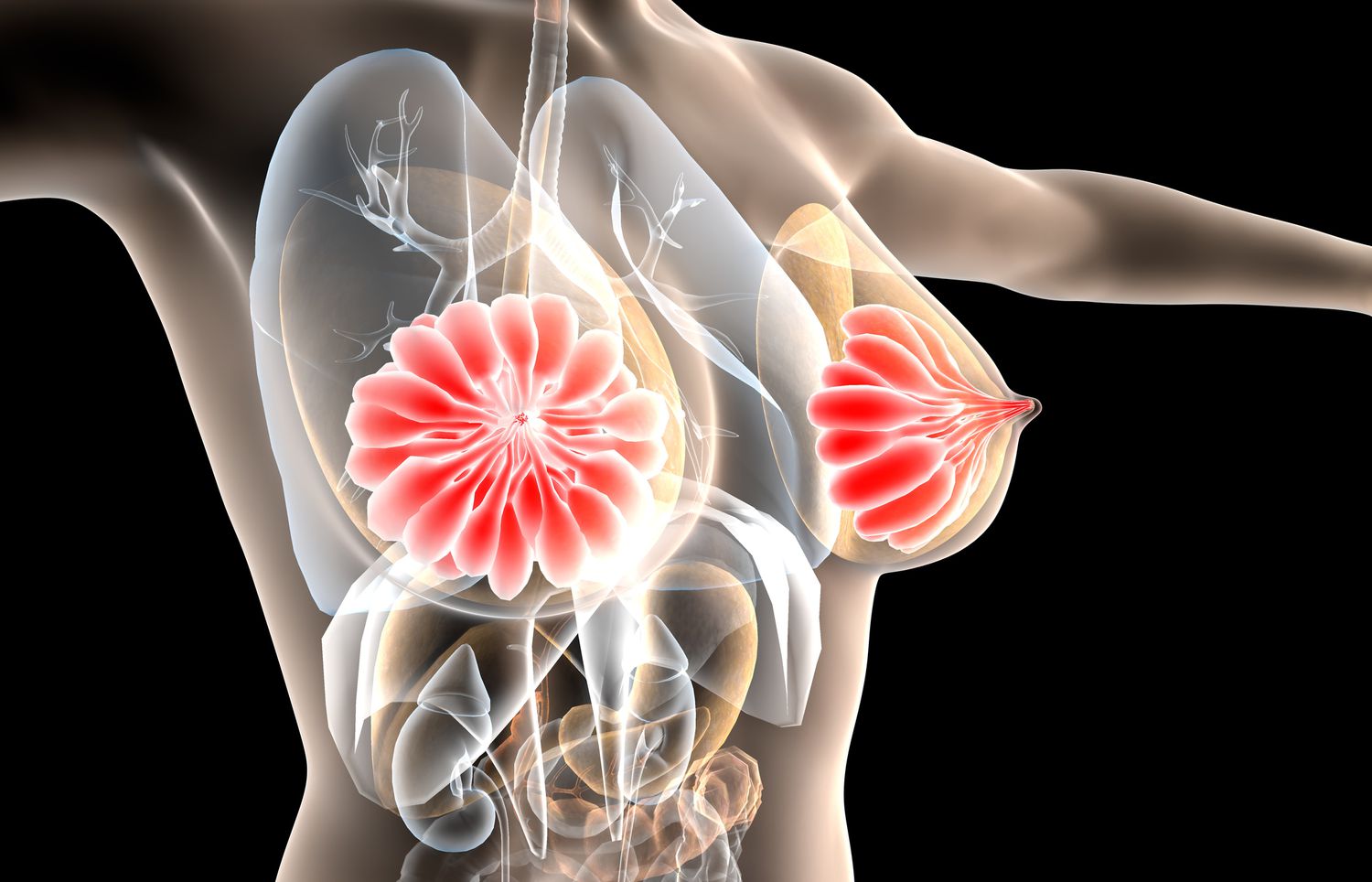

Dense tissue can obscure images on a mammography, which makes it more difficult to find tiny malignancies. Compared to women without thick tissue, those who have it are more likely to get breast cancer.

These characteristics mean that, in addition to the standard screening mammography, women with thick tissue may benefit from extra breast imaging. Your age, the precise density of your tissue, your preferences, and the presence of additional risk factors for breast cancer, such as a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, prior breast biopsies, or hormone exposure, may all play a role in the choice to have additional imaging.

Based on how breast density appears on mammograms, it is divided into four groups. “Decreased breast density” is what categories A and B are classified as, whereas categories C and D are regarded as having “more breast density.”

3D mammogram (tomosynthesis). This is performed at the same time as the traditional 2D mammogram. This translates to a lower recall rate, which means fewer women need to come back for additional views or unnecessary biopsies.

Whole-breast ultrasound. This has been used historically for women with dense tissue, although the added cancer detection rate is still low. The major downside is that whole-breast ultrasound has a fairly high false-positive rate.

Contrast-enhanced digital mammography (CEDM). This can be done at the same time as the traditional screening mammogram. CEDM uses an iodine-based contrast that is delivered through an IV prior to the test. This is a newer imaging strategy, so the research is not as robust. But initial studies have been very promising.

Molecular breast imaging (MBI). This is done separately from the mammogram and looks at blood flow patterns within the breast tissue. It requires IV administration of a radioactive tracer compound. MBI does have a small dose of radiation associated with it — more radiation than a mammogram, but not nearly as much as a CT scan. MBI is a great option for women with dense tissue who do not have a lot of other risk factors for breast cancer.

However, MRI is also the most costly and cumbersome of any test to image the breast tissue. Because of this, current guidelines recommend the use of MRI only for women at the highest risk of breast cancer. Specifically, these are women whose lifetime risk exceeds 20% to 25% based on factors such as family history, reproductive history and breast density. MRI does not have any associated radiation, although it does require an IV compound called gadolinium.

Many women are concerned about the increased dose of ionizing radiation with tomosynthesis, CEDM and MBI. Overall, the dose of radiation is quite low with breast imaging. The additional radiation with tomosynthesis compared with traditional 2D mammography is so low as to be nearly negligible. CEDM and MBI both add to the overall radiation dose, with CEDM comparable to having an additional mammogram that year and MBI a little higher than mammogram, but not nearly as much as a CT scan.

The decision to pursue any of these options should be made on an individual basis, using shared decision-making with a health care provider. For women who have a family history of breast cancer or other strong risk factors, validated breast cancer risk assessment tools should be used to calculate breast cancer risk and guide decisions on breast imaging. In the absence of a family history of breast cancer, the use of additional imaging is considered optional but may still be appropriate for many women, especially those with extremely dense tissue.